Today I’ve got three translated texts that are similarly interactive and engaging for a reader. Here’s the conundrum, though. If I had to make a guess, I’d say there’s a chance that most would be somewhat familiar with the series I mentioned above. But I’d be shocked if more than twenty percent of you were equally as familiar with any, let alone all, of the books I’m including in today’s post. Don’t worry, this time last year I would have been firmly in that “never heard of” camp for all of them.

The question then is why? I’ll be perfectly honest upfront and say that I don’t have a solid answer to that question but through my research, I’d be willing to hazard a few guesses. But first, let’s take a closer look at the three I’m including and see if I can convince you they’re just as worthy of readerly love as those others.

By: Masayuki Sebe

Translated by: Kids Can Press (Publisher)

This is the third in a “100” series from Japanese author Masayuki Sebe that combines a story with seek and find elements. It’s lunchtime for 100 monkeys and they’re all out of food. They all set out to find food and end up on a day-long adventure of food, play and escape from a monster! The story is simple, only a sentence or two per page to lead the reader on. But I think that simplicity is key because it offers an explanation of what is on the page but isn’t pushing the reader to flip to the next page in anticipation of what’s next. Instead the reader has plenty of time to examine everything else on the page without losing the storyline. And there is so much to look at!

Each two-page spread features all 100 monkeys. (Trust me, my kids have counted.) Most pages also have a few additional hidden objects the reader can find. Many monkeys also speak, asking the reader to find other monkeys or objects they describe on the page. If that’s not enough, there’s also a short list in the back of the book that notes additional characters that can be found on specified pages. There are even hidden objects made up of hidden objects – can you spot it?

The seek and find aspect is much more manageable for a younger reader than Where’s Waldo? or some other I Spy books. It’s bright, colorful and silly; some of the monkeys wear clothes, drive vehicles and behave in other un-monkeylike manners. Even right now as I have the book sitting out beside me I keep getting distracted, wanting to find some of the objects the monkeys are asking about. (And I’m definitely not the target audience for this book!) I haven’t had the opportunity to read either of Sebe’s two other 100 books, but from what I’ve seen they are similar in nature. If you have “seek and find” lovers in your house, this may be a series to consider checking out!

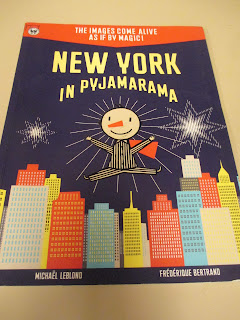

By: Michael Leblond

Illustrated by: Frederique Bertrand

Translated by: Unknown (Published by Phoenix Yard Books in the UK)

I’m not sure I remember how I came across this specific book. I do know that there was no way that I was going to let little things like the fact that no library in my state contains a copy or the fact that it was never published in the United States keep me from getting my hands on it after I read the description that said “sliding a striped acetate rectangle over the images makes them move astonishingly - wheels spin, spirals whirl, and traffic, as seen from the air, moves through the streets.”

Um, what? A book where I can make the illustrations actually move?? Yes! Fortunately for you (and me because I couldn’t possibly do it justice in pictures and my own words) there is a great video that shows just how the book comes to life! Before I go any further, go watch it here.

Isn’t that so cool?!?!?! I did a little more research and the effect is created by Ombro-Cinema, a type of barrier grid animation. The lines embedded in the design create an illusion of movement when contrasted against the lines of the acetate making it appear that the illustrations are animated when you pass the acetate over the top.

The use of primary colors with the black and white necessary to make the animation work pop off the pages. Early on in the book the reader changes the orientation from horizontal page flips to vertical, another interactive feature of the text that makes it feel different and unique. Many of the lines rhyme, where similar to 100 Hungry Monkeys then, the text seems to support the illustrations as opposed to being the driving force behind the story. If you like this one, there are other in the books in the series. Interestingly, I found multiple sources that stated this was the fastest-selling picture book in its source country of France in 2011. Did you know about it before now?

Translated by: Unknown (Published by Big Picture Press 2013)

In a few weeks we’ll be taking a closer look at wordless picture books (and yes, we can debate then if they can technically be considered translated) and I strongly considered holding off and sharing this title then. From the first moment I got my hands on it, though, there was no doubt that it was going to be one I had to include.

First published in Poland in 2010 by husband and wife team Aleksandra and Daniel Mizielinski, this is a story that can be “read” 100 different times in 100 different ways. You open the book to this:

It’s a full two-page spread, welcoming the reader to the world of Mamoko and introducing all the characters that appear in the story. Each character then has a question the reader is asked to consider (For example, Lionel Mane knows that one lion’s junk is another lion’s treasure. What does he make with his hidden gems?) The instructions on the page are to “use your eyes and follow the adventures of each of these characters in every scene.” There is also mention to search for some additional items, to note if any items seem out of place and think why.

I’ll admit I was a little overwhelmed the first time I looked at all the characters. How was I going to keep them straight? How was I going to remember what Lionel Mane was making with hidden gems as opposed to what fell out of Boris Greenshell’s bag? Fortunately, I quickly figured out that I didn’t have to! It was way more fun to pick just one character at a time and follow their story through the whole book and then start all over again at the beginning with another.

Additionally, it was up to me as the “reader” to determine what happened between the pages as well. What was the rest of their story? Could they perhaps have encountered another character between the pages? Did that change where they went from one scene to another? How did the characters that did interact in some way on the page change because of who they encountered?

The possibilities, as you can see, are endless! It was fun to not only find the characters from page to page but also to tell their story in whatever way I as a reader chose along the way. This was a book I could easily see an imaginative child interacting with for quite some time and I saw a lot of potential for its use in a classroom setting as well. In an ideal world where I had lots of time, I’d love to pick one character, give the book to a handful of kids and ask them to either tell me or write the story of that character and then compare the differences and similarities of each child’s story. One step further, if I could speak Polish (other than pierogi and paczki, which my dad and husband will now be begging to make soon after they read this post) I would love to hear a character’s story from a child in the country the book originated from and be able to compare it to an American child’s version of that same character. I wonder if there are any cultural contexts in the images that a “reader” in the source language would pick up that would not translate in other cultures. It’s a rabbit hole, I know. So another blog, another day…

If this book interests you, there are two other Mamoko titles to check out, The World of Mamoko in the Year 3000 and The World of Mamoko in the Time of Dragons . Both books feature the same set of characters off on new adventures for readers to imagine. Other similar offerings from the Mizielińska’s include Maps and H.O.U.S.E.

Hopefully I’ve at least piqued some interest in checking out any of these books. They are captivating and engaging and I’ve already noted they are similar to some beloved American books. So then we’re back to that question of why. Why are those books so popular and these fall under most reader’s radars, if they even show up at all? Why is it that a book that was the top-selling picture book in its source country not even available on the US market? Why, even when presented with them, do readers still tend to favor the American titles?

First, to be fair, the American books that I mentioned at the beginning of this post have been around longer than any of the ones I highlighted. Perhaps they are better established and these too, over time will earn the respect and admiration they deserve. While my optimistic self would love to hop on that bandwagon, I, unfortunately, don’t think that’s the case.

At the same “Where the Wild Books Are” conference I mentioned in Tuesday’s post, Betsy Bird, youth materials specialist at the New York Public Library (and one of my favorite children’s lit bloggers!), probably summed it up best; “We just don’t care.” That hurts my heart to write, but I think she’s onto something. There is at least a strong indifference related to actively seeking out international picture books. Bird went on to suggest that what is needed to overcome the indifference is two-part: “We need to overcome this gross distrust of illustrations and topics that are literally foreign to our picture bookshelves, and we all need to work on stamping out our own prejudices.” I also think it’s worth noting that she pointed out that a lot of the indifference stems not from child readers, but the adult gatekeepers, saying “On the picture book side, kids love [works] that don’t originate here—if we let them.”

That being the case, I’m going to make a plea to all you gatekeepers out there that are reading this. And it’s a plea I’ve been making since the beginning of this project and will continue to do so. If any of these books appeal to you in any way, or if there is a child in your life that you think may enjoy them – go buy it. Or go borrow it from a library. Remember, this is coming from the girl who a year ago had at best a small handful of translated titles on her own shelves. Consider this a challenge to step outside your own box.

The creativity continues here on Tuesday with my next set of “Outside the Box” books. I’m off to go make sure there really are 100 monkeys on every page, but I’ll see you then!

Additionally, it was up to me as the “reader” to determine what happened between the pages as well. What was the rest of their story? Could they perhaps have encountered another character between the pages? Did that change where they went from one scene to another? How did the characters that did interact in some way on the page change because of who they encountered?

The possibilities, as you can see, are endless! It was fun to not only find the characters from page to page but also to tell their story in whatever way I as a reader chose along the way. This was a book I could easily see an imaginative child interacting with for quite some time and I saw a lot of potential for its use in a classroom setting as well. In an ideal world where I had lots of time, I’d love to pick one character, give the book to a handful of kids and ask them to either tell me or write the story of that character and then compare the differences and similarities of each child’s story. One step further, if I could speak Polish (other than pierogi and paczki, which my dad and husband will now be begging to make soon after they read this post) I would love to hear a character’s story from a child in the country the book originated from and be able to compare it to an American child’s version of that same character. I wonder if there are any cultural contexts in the images that a “reader” in the source language would pick up that would not translate in other cultures. It’s a rabbit hole, I know. So another blog, another day…

If this book interests you, there are two other Mamoko titles to check out, The World of Mamoko in the Year 3000 and The World of Mamoko in the Time of Dragons . Both books feature the same set of characters off on new adventures for readers to imagine. Other similar offerings from the Mizielińska’s include Maps and H.O.U.S.E.

Hopefully I’ve at least piqued some interest in checking out any of these books. They are captivating and engaging and I’ve already noted they are similar to some beloved American books. So then we’re back to that question of why. Why are those books so popular and these fall under most reader’s radars, if they even show up at all? Why is it that a book that was the top-selling picture book in its source country not even available on the US market? Why, even when presented with them, do readers still tend to favor the American titles?

First, to be fair, the American books that I mentioned at the beginning of this post have been around longer than any of the ones I highlighted. Perhaps they are better established and these too, over time will earn the respect and admiration they deserve. While my optimistic self would love to hop on that bandwagon, I, unfortunately, don’t think that’s the case.

At the same “Where the Wild Books Are” conference I mentioned in Tuesday’s post, Betsy Bird, youth materials specialist at the New York Public Library (and one of my favorite children’s lit bloggers!), probably summed it up best; “We just don’t care.” That hurts my heart to write, but I think she’s onto something. There is at least a strong indifference related to actively seeking out international picture books. Bird went on to suggest that what is needed to overcome the indifference is two-part: “We need to overcome this gross distrust of illustrations and topics that are literally foreign to our picture bookshelves, and we all need to work on stamping out our own prejudices.” I also think it’s worth noting that she pointed out that a lot of the indifference stems not from child readers, but the adult gatekeepers, saying “On the picture book side, kids love [works] that don’t originate here—if we let them.”

That being the case, I’m going to make a plea to all you gatekeepers out there that are reading this. And it’s a plea I’ve been making since the beginning of this project and will continue to do so. If any of these books appeal to you in any way, or if there is a child in your life that you think may enjoy them – go buy it. Or go borrow it from a library. Remember, this is coming from the girl who a year ago had at best a small handful of translated titles on her own shelves. Consider this a challenge to step outside your own box.

The creativity continues here on Tuesday with my next set of “Outside the Box” books. I’m off to go make sure there really are 100 monkeys on every page, but I’ll see you then!

No comments:

Post a Comment