As I mentioned the other day, the idea of covering a myriad of topics that fall under the category of “Human Rights” in one post is absurd. Even with my only covering translated picture books - still daunting beyond imagination. Additionally, I think that within the last few years we have been seeing an increased awareness and even publication of books that address these topics in the United States as well. I point this out because the most recent of the books that I’m including in this post was originally published in its source language in 2011 and the oldest in 2000. So while the world may be one step ahead of their decision to share with children books on xenophobia, the rights of children and LBGTQ+ themes based on those publication dates, I think the number of US titles that take on these topics, controversial or not, will continue to increase. (At least I hope it will!)

All that in mind, my offerings for today’s post are really some of my favorites or the ones that I felt were noteworthy for a particular reason. While I wish I could include so many of the other books I found, I keep reminding myself that the purpose of a blog is just to present some of the titles out there in hopes of increasing awareness of the benefits of reading the world. I’ve mentioned it before, but if you’re interested in other titles, leave me a comment or contact me via email. As an extra bonus, I’ll suggest two Australian titles which I know aren’t “technically” translated that feature characters that are refugees at the end of this post. But before that, let’s take a closer look at some books that really stood out to me for their unique approaches.

All that in mind, my offerings for today’s post are really some of my favorites or the ones that I felt were noteworthy for a particular reason. While I wish I could include so many of the other books I found, I keep reminding myself that the purpose of a blog is just to present some of the titles out there in hopes of increasing awareness of the benefits of reading the world. I’ve mentioned it before, but if you’re interested in other titles, leave me a comment or contact me via email. As an extra bonus, I’ll suggest two Australian titles which I know aren’t “technically” translated that feature characters that are refugees at the end of this post. But before that, let’s take a closer look at some books that really stood out to me for their unique approaches.

Translated by: © Eerdmans Books for Young Readers

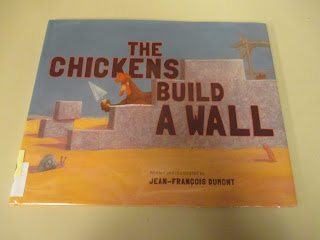

I first read The Chickens Build A Wall by French author Jean-Francois Dumont shortly after last year’s Presidential election. Remember how a few paragraphs ago I said that perhaps the world was one step ahead of us? This book, originally published in France in 2011, in my hands right then seemed like solid proof. The chickens in Dumont’s work, under the urgings of the rooster who ‘decided that this was the perfect occasion to take control of a barnyard full of hens’ determine the only way to protect themselves from a mysterious visitor (a hedgehog) that shows up one day, is to build a wall around the henhouse. Hmmm, sounds strangely familiar, right?

Dumont’s choice to personify animals who make decisions on how to treat each other based on ignorance and fear is a means of discussing xenophobia with young readers. While none of the barnyard animals know exactly what a hedgehog is, only the chickens react so extremely, turning to gossip, suspicions and outright accusations (which are proven false) to justify their reaction. The irony then becomes once the wall is built, with all the chickens safely inside, they learn that the hedgehog had been wintering in a pile of hay within the wall with them all along.

As with all the books in this category, the one thing I find it necessary to keep coming back to is the potential for them to be conversation starters. The fact that the political connotation or the term xenophobia may be beyond the age range the book is geared at doesn’t really matter. Even young readers are going to recognize that the chickens excluded the hedgehog because he was different than them. There’s obviously more to it than that, but it’s a start! It’s also very engaging, using humor and illustration to balance a complex topic.

Dumont’s other titles are similarly allegorical in nature. The chickens and other barnyard animals take center stage in two more social justice based books by Dumont, The Sheep Go On Strike and The Geese March In Step. Personally, I thought the text in Sheep was a little more advanced and the message a bit more didactic (the sheep strike due to unfair working conditions!), potentially failing to engage younger readers on the same level as Chickens, but I enjoyed the two-page spread illustrations more. I haven’t had a chance to read Geese, but the “be yourself no matter what” message at the heart of the story seems to match with the underlying theme of “treat others how you would want to be treated” that underlies Dumont’s work. The rat from the barnyard, Edgar also has his own story which I haven’t had the chance to read. I’m also anxious to eventually get my hands on Dumont’s most recent translated title, I Am A Bear, which tells the story from the point of view of a homeless teddy bear who lives on the street and shows how people react to him. If you want to know more about any of Dumont’s stories, I found this really great podcast from the publisher of most of his translated titles, Eerdman’s Books. Since how we treat people is really at the heart of human rights (duh!) I wanted to spotlight Dumont’s work because I think he tackles it at a child’s level with the use of animals and humor, but at the same time with a nod to the more perceptive reader who understands the underlying satire and irony.

By: Linda de Haan and Stern Nijland

Translated by: Unknown (The book does not give any indication as to the translator and the original US publisher, Tricycle Press, ceased publishing in 2011)

A full five years before the American picture book And Tango Makes Three by Peter Parnell and Justin Richardson found itself at the center of censorship debates on same-sex marriage, adoption and homosexuality in animals, King & King by Linda de Haan and Stern Nijland was published in The Netherlands. The book, tells the story of Prince Bertie, who must find a princess to marry, according to his mother the Queen who is ready to hand over the realm. Though he’s “never cared much for princess”

Prince Bertie agrees and a peck of potential princesses are paraded past the pondering prince (It’s a fairy tale, forgive my whimsy). With the arrival of Princess Madeline, Bertie realizes he has found “the one” – Madeline’s escort and brother, Prince Lee, as they both instantly fall in love with the exclamation “What a wonderful prince!” The two marry, becoming King & King, allowing the Queen to retire. Their happily ever after ends in a kiss, the first ever illustration of a gay kiss in a children’s picture book.

It’s not surprising that the book came from The Netherlands, as it is considered one of the most progressive nations in the world regarding LBGTQ+ rights. It became the first country to legalize same-sex marriage in 2001 and a 2015 European Union member poll found that 91% of residents of The Netherlands supported same-sex marriage. Not so in the US when it was first published here in 2003. The book soon found itself on many challenged and banned lists. It was the catalyst behind the Parental Empowerment Act which called for national boards composed of parents to review books purchased by elementary schools and would have prohibited states that did not do so from receiving federal education funding (it thankfully died in committee). It was also the book that led to the creation of an anti-gay lit resolution in Oklahoma and was the source of a number of major federal lawsuits. As recently as 2015, a teacher in North Carolina resigned over the backlash that ensued over his choice to read the story to his class of third graders after he perceived negative gay stereotyping among his students.

The amount of controversy surrounding the book is not why I chose to share it, though. I mean, this is the controversy category, a lot of the books in this category make at least some people uncomfortable about sharing them with children. And maybe not even because they don’t agree with what it is about, but perhaps because they’re not ready to answer questions they might spark in young readers. No, I chose it because of the medium it chose to tell the story.

If you think back a couple weeks, my first category was full of fairy tales, folklore and mythology and I repeatedly mentioned that it seemed like the logical place to start because of how universal such stories are. Variations of a singular tale that share similar motifs exist across the world. I noted that this was a way for a reader to connect what they already knew as familiar. That is part of what makes King & King unique, by drawing upon classic elements familiar in the canon of children’s literature, it celebrates and identifies with a marginalized culture. This idea was further explored by Amy T.Y. Lai in her 2010 essay “Waiving the Magic Wand: Forging greater open-mindedness by subverting the conventions of fairy tales” in which she notes King & King “subvert the conventional fairy tale by including many unconventional elements” and works to “ try to influence their readers and help bring about changes in existing laws that oppress gay people.”

So my purpose behind sharing this title is because I think that King & King is a pioneer. It certainly is no longer the only (or even the best) choice out there to represent the need to give each individual respect and equal treatment, regardless of their sexual orientation. Also, as a slight rabbit hole, it is also worth noting that there was a follow-up title, King & King & Family.

What I found incredibly interesting is that the book was written at the request of the American publisher, Tricycle Press, and was first published in the United States. There are many positives to the story; King & King adopt a little girl, the family is multi-racial, the illustrations are even more colorful than the first book. But for me personally, it felt more forced than the first book, as if it had an agenda. After I learned about why it was written, I wonder if that may have something to do with it. Just a thought, and again, just my personal opinion. The second book too could be considered a pioneer, I’m just not sure if it is as impactful as King & King.

By: Alain Serres

Illustrated by: Aurelia Fronty

Translated By: Helen Mixter

As with the previous two books, my third selection looks at a topic where it seems the US is behind the rest of the world in their stance on a certain area of human rights. French author Alain Serres, who is known for books dealing with human rights, especially those of the child, pairs with illustrator Aurelia Fronty, to present the concept of human rights (specifically those of children) as set forth in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. The vibrant illustrations accompany a text told from the point of view of a child describing what it means to have rights that range from the right to have food, water and shelter, to the right to be free from violence.

The children in the illustrations are each unique, different skin tones, sizes, styles of dress – it is truly a global image of childhood and that the rights described are for each of those children no matter where they come from.

The book, as noted, is based on the 54 articles that the Convention laid out, which are based on “non-discrimination (the rights apply to all children), what is best for the child, the right to live and grown in good health, and the right for children to express their opinions in matters that concern them” (afterward of text). In the afterward that follows, it is noted that 193 states are party to the Convention, having agreed to make changes or new laws that will support it. This does not include the United States who signed to show their support but has not ratified it. If I were to hazard a guess, it is probably not the content of the articles that is the source of the disagreement but rather the monitoring and compliance that is the reason it has yet to be ratified. But all of that is definitely another blog for another day. Whatever the case may be, it makes me sad to admit that before I came across this book I was unaware of that we as a nation had not joined with the rest of the world to fight for such an important cause, thus why I thought it was an important one to include in this post.

(Kristi’s extra thought: Though not translated, We Are All Born Free and Dreams of Freedom are two other phenomenal choices that look at human rights and feature the works of international artists and illustrators. Both are based on the 30 rights set down in 1948 by the United Nations.)

Like I said from the outset – this is a huge topic to cover. What I found most important to highlight where some of the areas that I think the US is still behind the rest of the world and offer up some worldly titles that we can then use to fill those gaps. I did promise two more bonus titles. Both are from Australia and are stories of children that are refugees. If this is a topic that is of interest, I highly suggest checking out My Two Blankets (and pay close attention to the use of color!) and Ziba Came On A Boat. I can vouch for the fact that there are even more recent US titles on this topic as I’ve been collecting them for my amazing group that I am so proud to be a part of, Literary Activists @ EMU. (You can find us on Facebook and Instagram!) We are going to be doing helping at an event hosted by the Ypsilanti library on November 4th featuring some of these stories as well as a reading of Lost and Found Cat by author Amy Shrodes. If you're in the area and interested in attending, check out the information here.

In the meantime, we’re almost finished dealing with controversy! I’ll be back on Friday with one more post looking at some books that deal with emotions. Then next Tuesday we’ll be going “outside the box” with some dual language books.

No comments:

Post a Comment