To look at the importance of artwork in my section on fairy tales and folklore, I’ve picked multiple books by two different authors. Their approaches and actual art are vastly different which is one of the reasons I felt strongly about sharing them. I’ll admit that on my initial browse the first had me a bit perplexed while the second I adored. After closer inspection and research, the waters were a bit muddied though. I had so much more respect and appreciation for the first, and while I still loved the second it raised more questions than answers. But perhaps I’m getting a bit ahead of myself and should just dive right in!

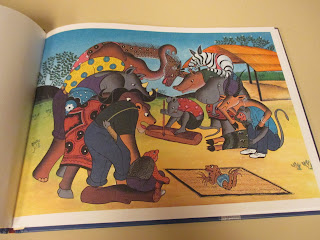

When I first picked up my copy of John Kilaka’s, The Amazing Tree and then True Friends the art work jumped off the page. It is full of bright bold drawings of animals decked out in bright bold clothing that at first glance made me wonder if perhaps the book had been produced in the late 60’s as I’m pretty sure that’s the only place I’ve ever seen some of those patterns and colors before.

I honestly wasn’t sure what to make of it other than the fact that it definitely got my attention and made me want to read the book and then figure out where it came from and what that might say about the book and its art.

It didn’t take me too long because when I got to the back cover, there was a note from the author that read:

It didn’t take me too long because when I got to the back cover, there was a note from the author that read:

“This story comes from the Fipa tribe of southwest Tanzania. It was told to me and recorded in the Fipa language (my native tongue) on July 2, 2007. I then translated it into Kiswahili. From Kiswahili my son, Kilaka Kenny translated it into simple English. It was then adapted into reading English by North South Books. “ (The Amazing Tree, John Kilaka)

Part of the mystery was solved! Kilaka was born in Tanzania and has spent a good deal of his life traveling the country collecting folk tales from various tribes. If you have a few minutes I highly recommend this article in which he discusses his experiences collecting tales. He notes that the oral nature of these tales means he has to actually find someone who knows the tale which can be challenging and doesn’t always end in a story. The effort by Kilaka, though, now means that these once oral tales will be preserved not just for the people of Tanzania but around the world. That Kilaka further pinpoints the exact tribe the story comes from is important because as the African Studies Center at the University of Pennsylvania notes “Each ethnic group has a store of myths, legends, folk tales, riddles, proverbs, and sayings that embody culture and tradition and are an important element in Tanzanian cultural heritage.”

While this information gave me a new appreciation for the words of the page it still didn’t quite explain those colorful creatures.

Part of the mystery was solved! Kilaka was born in Tanzania and has spent a good deal of his life traveling the country collecting folk tales from various tribes. If you have a few minutes I highly recommend this article in which he discusses his experiences collecting tales. He notes that the oral nature of these tales means he has to actually find someone who knows the tale which can be challenging and doesn’t always end in a story. The effort by Kilaka, though, now means that these once oral tales will be preserved not just for the people of Tanzania but around the world. That Kilaka further pinpoints the exact tribe the story comes from is important because as the African Studies Center at the University of Pennsylvania notes “Each ethnic group has a store of myths, legends, folk tales, riddles, proverbs, and sayings that embody culture and tradition and are an important element in Tanzanian cultural heritage.”

While this information gave me a new appreciation for the words of the page it still didn’t quite explain those colorful creatures.

I quickly discovered that Kilaka had been trained and worked in a specific art style that had originated in Tanzania, Tinga Tinga. It was created by Edward Tingatinga in the late 1960’s and is known for using enamel colors and highly decorative patterns. After Edward’s death, his family created the Tinga Tinga Cooperative to train artists in the style. Only artists that have trained at the cooperative are allowed to be considered Tinga Tinga artists, a list which includes John Kilaka! In this way not only is Kilaka recording the Tanzanian tale but is preserving a style of art with origins and importance to the country as well.

A second and all subsequent read throughs have been strikingly different than my initial impressions because of this understanding. Every time I stop and consider how many hurdles these books had to overcome to end up in my hands I’m a little blown away. No road to publication is easy, but if Kilaka hadn’t stumbled across that one story teller on July 2, 2007 the tale may have never made it outside of that village.

And as I said at the beginning of this post, the artwork is what really brings each of the books to life. It’s also worth noting that Kilaka’s work as a children’s author has twice won him the Peter Pan Silver Star, awarded by IBBY Sweden.

My second author has had his own share of success, winning the Sankei Children’s Book Award, exhibiting at the Bologna International Picture Book Exhibition on multiple occasions and having his work translated into more than half a dozen languages – everything from Polish to Taiwanese! Japanese author and illustrator Taro Miura has thirty-six different books to his credit listed on his home page, including seven that have been translated and published in the United States. It’s his book Tiny King and it’s prequel (which was written and published later), The Big Princess, that fall squarely into my fairy tale category.

The Big Princess by Taro Miura

The Tiny King by Taro Miura

(Kristi's Note: I did a lot of searching but was not able to find the name of the translator for either of these two titles. This isn't uncommon, unfortunately. I spoke to one publishing company that told me that it's just translated "in house" so no one is credited. It's an issue we'll get back to, I promise)

From Princess

To Queen

The King is also marked with a letter (K) but it is his left pant leg that’s worth a second look as it is actually a piece of his wedding announcement to the Big Princess. Miura also mixes his cut-out shapes with actual images of objects and black and white sketches in both books. Also especially striking in The Tiny King is the use of color. Until The Big Princess shows up in the Tiny King’s life, everything is dark, all the backgrounds are black and the King himself is usually the most insignificant detail on the page. This shifts dramatically with the future Queen’s arrival to whites, pinks and oranges with the King engaged in the action instead of alone. With these details Miura adds layers to the story without actual words – a rather sophisticated technique that makes this an appealing read for any age.

If I haven’t made it clear with my gushing, I’m definitely a fan of Miura’s work in these two books, and I don’t want to give away too much of the story because these are definitely ones I would suggest reading. Multiple times in fact as I’m still finding new and interesting things to note every time I pick either of them up. But one thing has been gnawing at the back of my brain since I first read both of these books that I want to at least mention. While the geometric figures reminded me vaguely of the paperfolding art, origami, to me there was a decidedly Western feel to the characters represented in the stories. The Princess/Queen struck me as the stereotypical blonde and all the people, from her parents to the children she and the King have white skin.

There is no diversity and no nod to the culture it hails from. I discussed this with a few of my classmates who are more familiar with Japanese literature and art in the form of anime and they told me that, in their experience, this was somewhat common. After a little further thought on my part I also reasoned that perhaps this was Miura’s nod to the stereotypical representation of characters in modern fairy tales.

I was almost willing to let it go without mentioning it here, but when I took a look at some of the other examples of Miura’s work via his website I noticed that many of the human characters he depicted were very similar to those in The Tiny King and The Big Princess. What struck me even further was that many of Miura’s books are board books, meaning their very simplistic, with very few words and are mostly pictures, intended for non-readers as a learning tool. It didn’t sit quite right that the earliest exposure some Japanes children might be having via these books would appear to be lacking any form of diversity. Again, I am no expert period but my knowledge of the Japanese publishing industry and what is the norm for the diversity in board books there is pretty much non-existent. I'm in no way suggesting this is "wrong" it just caught my attention. This could very possibly be par for the course in books published there or maybe I just haven’t seen enough of Miura’s work beyond what I’ve read (I was able to get my hands on two other books of his, Tools and Bum Bum and found similar representation, though there are far fewer human elements in either of these books period.) – I honestly don’t know and as much as it piques my curiosity that is another blog for another day. I do know though that part of this project of mine is to push me to ask questions, think outside the box and sometimes be OK with not having all the answers.

So take my little side note there for what it is – a rabbit hole that I’m not suggesting any of us need to tumble down, just to be aware that it’s there to possibly come back and explore some time in the future. In the meantime, I highly suggest getting your hands on copies of The Tiny King and The Big Princess and see what else you can discover in Miura’s work.

I’ll be back on Friday with the last post in the fairy tale and folklore category where I’ll be taking a closer look at some books that highlight common types of roles we often see characters play in these types of stories.

No comments:

Post a Comment