(The back of my desk, a reminder every time I walk into my office)

So begins some of the most well-known tales in

literature. Note that I said literature

– not children’s literature. The

earliest written version of the classic fairy tales and folklore from around

the world were never truly

intended entirely for a younger audience.

But for these purposes let’s agree to set that entire debate aside as

well as the argument surrounding the origins of this type of literature. I’m

going to let the much smarter literary critics debate the poly-genesis vs.

mono-genesis controversy and I’m also going to keep our focus to the earliest

written versions of these stories. There

is no arguing the fact that they existed in many different forms well before

Grimm, Andersen, Perrault and a myriad of others put them on paper, but another

blog, another day…

To that same end, as Dr.

Gillian Lathey an expert in the field of translated texts for children, notes

in her recent text Translating Children’s Literature, as

a whole, children’s literature is often adapted, retold and abridged due to its

“popular” nature. This is especially

true with fairy tales. As she states

“The free translation and alteration of popular children’s stories has led to a

proliferation of versions. Characters belonging

to a children’s canon that is familiar across the world such as Cinderella,

Pincocchio, Alice, the Moomins, Winnie-the-Pooh and the Little Prince,

encourage the common perception that children’s literature is an international

literature.” (113)In other words, the

very nature of these stories lead them to be told, shared, adapted, re-told and

then changed again.

Additionally, I did mention the other day how important it

is to remember that the majority of these tales were passed orally long before

they were ever actually written down.

Further, once they were written down, they went through many different

variations even by the same author. The

Grimm brothers were notorious for this as can be seen in this side by side comparison of

the 1812 and 1857 versions of Hansel and

Gretel. While I could spend a great

deal of time postulating the “why” behind this, it’s probably safer to concede

this to another blog, another day as well.

And that’s to say nothing about the changes that have been made to the

stories since then - you can find many different translations of a single tale

that vary greatly. Take the Grimm’s Aschenputtel (Cinderella) for example –

some translations completely remove the step-sisters mutilation of their feet

or the doves pecking out their eyes on grounds that it is too gruesome for

young readers. This means that not only

are many readers not even aware they are reading a translation in the first

place, but, as Lathey points out “nor are most readers aware of the degree to

which translators, let alone retellers and adapters, have altered the German

source texts of the Brothers Grimm, merged different versions of the same tale,

or drawn on exiting translations.” (115)

So those “simple little fairy tales” we know and love, perhaps not so

simple.

(Kristi’s full disclosure: I love fairy tales and folklore. I planned an entire semester at school and

home around the ability to take a class on the topic. I did a major project on Raisel’s

Riddle as a Jewish adaptation of Perrault’s Cinderella. My favorite

author, Adam Gidwitz, penned the this

year’s Newberry Honor winner The

Inquisitor’s Tale (which swaps spots with Charlotte’s Web as my favorite book) but it was his Grimm trilogy that

knocked my socks off. My nine year old son and I still giggle every time we think about how Gidwitz translates Aschenputtel. Fairy tales rule.)

Fairy tales, folklore and myths seem like an obvious place

to begin to look at translated tales for a few major reasons. First and foremost, it’s important to

remember that nearly all the favorite classic tales are in and of themselves

translations to our English-speaking selves.

In fact, Andersen and the Grimms both find themselves among the top

10 authors translated into English.

Oddly enough though, these are not the versions most Americans are

familiar with thanks in large part to Disney’s adaptations of the

classics. If your “once upon a time”

ends in “happily ever after” it’s fairly safe to assume that you’re not reading

the earliest recorded versions of many of these tales. No, those tales are much more likely to be filled

with murder, cannibalism, anti-Semitism and child abuse – perfect bedtime

stories, right?

Even so, nearly every culture has their own variations of

the most well-known of these stories. If

one of the main “purposes” of translation is to expose the reader to other

cultures and perspectives, what better way to do so than through a fairy tale or

folklore that shares common elements with a story they are probably already

familiar with? Granted, this is a very

simplistic interpretation and is by no means the only (or in my opinion most

important) reason for translation. But

for publishers worried about the “strange and unfamiliar” aspects of foreign

literature scaring away potential readers, fairy tales seem like a much safer

road given that familiarity. This is

probably the reason that a large chunk of the literature translated for

children often tends to fall in this category.

When I first started to organize my categories, the

following was what I came up with for what we’ll be discussing over the next

few posts:

Folklore, myths, fairy tales – they are the building blocks

of cultures, language and literature worldwide.

And without diving too deeply into the debate of whether they evolved

under polygenesis or monogenesis, there is no denying that similar stories (for

example a creation story) are part of nearly every culture that ever

existed. Further, those stories very

often share similar characteristics that allow for a basis of comparison. The similarities allow the connection to be

seen and the differences allow us to learn about the culture they come

from. These types of stories are a rich

source of material when it comes to translated texts because there is a desire

to learn about other cultures through the stories that are woven into the

fabric of who they are – they connect us.

We come across these stories all the time without every even realizing

we’re being exposed to a translated tale (thank you Disney!). For this category I strayed from those most

common tales into picture books that combine pictorial elements of their

culture with the story.

A few things to keep in mind with the material from this

category; just like there is debate over where these types of stories started,

there is much debate surrounding the original (written) authors of some of the

literary versions. I have tried to give

credit where credit is due in comparing some texts, but in some cases have used

the most well-known version as a base for comparison. Secondly, I know there are HUNDREDS of tales

that could potentially fall into this category.

I have tried to pick ones that are important for both the story and the

art given the fact that I am focusing on picture books. If you know of other versions, please

comment! As I said, if you’re looking

to begin to dabble in translated literature, this is an easy starting

point. If fact, you may have already

been doing so without even realizing it.

Hopefully my suggestions as well as others may spark an interest to go

beyond those most widely known versions.

Thirdly, I love Disney as much as the next child born in the eighties

who can sing every word to The Little

Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, and The Lion King (and now Frozen

thanks to the next generation that lives under my roof) but these are NOT the

original tales and should not be considered as such. Yes, most are based on some of the early

written stories, but they have been greatly changed and “sweetened” up to make

them “more palatable” for children.

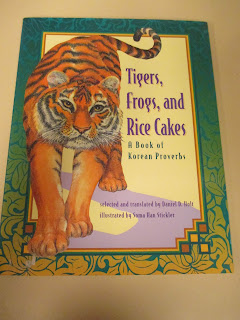

A late edition to this post, but consider it a sneak peak at some of the wonders to come. I was at the Kerrytown Book Fest this Sunday and snagged a couple beautiful books for my collection. Even though I already have my books set for this category, I found one that I knew I had to share.

Also, the back of the book lists all of the proverbs and an explanation as to their meaning. There is an additional note from the publisher that credits Song Que Hahn for assistance as to the translation and meaning. The illustrator was also born and lived in Korea until she moved to California in the mid 70's. It's important to note how all of these items together add authenticity and accuracy to the work.

A late edition to this post, but consider it a sneak peak at some of the wonders to come. I was at the Kerrytown Book Fest this Sunday and snagged a couple beautiful books for my collection. Even though I already have my books set for this category, I found one that I knew I had to share.

Selected and Translated by: Daniel D. Holt

Illustrated by Soma Han Stickler

I haven't had a lot of time with it, but I knew I couldn't pass up the opportunity to share it even in a limited capacity. There is a wonderful explaination from the translator about the usage of proverbs in Korean society and he notes "by comparing proverbs across cultures, we can identify some of the similarties and differences that help us appreciate the diversity that characterizes the world."

Note the text is bi-lingual, appearing in English and Korean

Also, the back of the book lists all of the proverbs and an explanation as to their meaning. There is an additional note from the publisher that credits Song Que Hahn for assistance as to the translation and meaning. The illustrator was also born and lived in Korea until she moved to California in the mid 70's. It's important to note how all of these items together add authenticity and accuracy to the work.

In the next couple of posts I’ll be taking a closer look at

adaptations of some of the most well-known fairy tales, a closer look at the

importance of art that is associated with the place or culture the book

originated in and some fairy tale and folklore characters from around the world

that we may not be familiar with but fill roles (such as the hero or the

trickster) that is a commonality in many of this tale type. Again, I look forward to other suggestions

and comments others may chime in with!

And fairy tales still rule!

No comments:

Post a Comment