Without diving too deeply into the arguments about “original vs. re-telling vs. adaptation”, I’m going to come out and call the tales that I’ve included in this post adaptations. To me an adaptation blends the original tale with something innovative to produce a new and unique story. The core, the heart of the original tale is still there and recognizable, but it is a completely separate entity. If the original tale is the parent, adaptations are all their possible offspring; they share traits and features but they’re definitely not the same person.

The Flight of the Mermaid by Sirish Rao (Author), Gita Wolf (Author),

Bhajju Shyam (Illustrator)

Let’s start with one that doesn’t stray too far from the original tale. Published in 2009 by Tara Books in India, The Flight of the Mermaid follows fairly closely to the Hans Christian Andersen version. Not Disney - no talking seagulls or domineering fathers here, trust me. In fact, this adaptation presents a much more modern and feminist ending where our mermaid friend doesn’t get the boy she’s been pining after but comes to realize that perhaps there is something even better for her yet to come. We’ll get back to that in a minute but first, I’d be remiss to not mention the other major reason I’m including this book – the art done by illustrator Bhajju Shyam.

A member of the Gond tribe in Central India, Shyam’s illustrations are based in Gond tribal art. It is so striking that I considered it another component, aside from the changes to the words of the story, that makes the tale an adaptation. You’ll hear me make this argument again later when we get to the Wordless books but I think that when considering picture books they are almost translated twice – once by a third party through the words of the story and then again by the reader when they view the illustrations. Not only is the text unique to the culture but in many cases so is the artwork. The good side to this as that the reader is exposed to the culture of origin, the bad is that it sometimes causes these books to be labeled as weird, odd or not something that American readers would enjoy because it’s not something we expect out of a picture book that originates here. (I mean, the above illustration is not what probably pops into your mind when you think "Little Mermaid," right?) In the world of translated literature this is yet another hurdle a picture book has to leap before it is published here.

(Kristi’s side note: To be fair, like many of the books that I am including in my project from India, it was written and published in English. I am including this (and others) for a few reasons: 1) they were published in India FIRST and then in the United States 2) there are so many different cultures in India given the size of the population and books published from there can give us insight into many of them 3) as I said above, the artwork – I honestly considered doing an entire category on books that I felt the artwork was why they were published in the United States as the itself often paled in comparison and 4) it’s my project, see Disclaimer #1!)

Female empowerment seems to have become a common trope in modern fairy tales around the world. Not only does it rewrite Andersen’s The Little Mermaid in the story mentioned above, but French author Marjolaine Leray reimagined Little Red Riding Hood in her book Little Red Hood.

Little Red Hood by Marjolaine Leray

(Translated by Sarah Ardizzone)

She never appears helpless or even afraid of the wolf, in fact you never see her eyes at all and most images of her are in profile and two-dimensional. The wolf, in contrast, towers over her with claws, teeth and bravado. None of this phases Red who questions the wolf’s personal hygiene (she tells him his breath smells!) to entice him to eat the poison laced candy. I also thought it was interesting that the artwork appears rough, almost quick sketches that only appear in black, white and red.

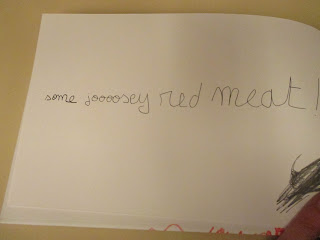

Additionally, in what is perhaps a nod to the macabre nature of the story, all the text is hand-written in cursive, suggesting perhaps that it is better meant to be read by someone able to read cursive, with the wolf’s dialogue in black and Red’s in well, red. I did manage to actually get my hands on a copy of the original book and found this was true in the French AND English version.

It is interesting to note the spelling of "juicy" here. In my French copy it is "de la viande rouge et saignante!!!" which translates to "red and bloody meat" meaning it was the two time Marsh award winning French to English translator, Sarah Ardizzone's, choice to phrase it as above. While I'm just pondering here, part of it could have to do with the way the english phrase fills the space on the page as it would have to work within the existing illustrations. It could also be to give 'voice' to the Wolf's character.

by Rita Jahanforuz (author) and Vali Mintzi (Illustrator)

Written by “the Madonna of Israel,” Rita Jahanforuz, the story contains the familiar evil step-mother and step-sister who treat our heroine, Shiraz, as a servant. Without giving too much away (because you need to read this one!), the story changes when Shiraz is rewarded with beauty not for listening to spoken words but the unspoken desires of the heart, a lesson lost on her step-sister whose actions cause her to be mistaken by her own mother for a beggar. Without being preachy or didactic, the story ends with the reminder that people “do not always know how to ask for what they need.”

The illustrations, done by Vali Mintzi are bright, bold and full of details that add to the text. In this adaptation the reader can see connections to the original tale but they are not as clear cut as the first two. In fact, on my first read through I immediately connected it to Cinderella in the first few pages but then noticed a marked evolution into a completely different tale which takes major detours from what we “know” as Cinderella. It made me wonder if perhaps Jahanforuz used some of the major plot points from the classic to connect readers to her version to share a new moral that contained a modern and needed message. One purpose of these first three adaptations very well may be to serve as commentary on the world they were written in and for. Interestingly, considering they were translated, it also then suggests that those stories serve a purpose globally as well.

One last book to share hails from Japan though this version was written in French and first published in France in 2013 and then in the U.S. in 2014.

Issun Boshi: The One Inch Boy by Icinori

Translated by Nicholas Grindell & Co.

The publisher describes Issun Boshi: The One Inch Boy as a classic Japanese fairy tale that “tells the story of Issun Bôshi, the tiny son of an old, long childless couple.” Sound familiar? On my first reading it definitely reminded me of Andersen’s Thumbelina or the English folktale Tom Thumb. Interestingly, the Japanese version of the folktale seems to predate both of those. What struck me most about this version from Icinori, the French illustrators Mayumi Otero and Ralphael Urwiller was that I would never in a million years guessed that it was published in 2014 when I pulled it off the shelf at the library.

I’ll be back on Tuesday with some really neat books from Tanzania that created a brand new art form and a look at a pair of Japanese books that blend Western and Eastern art.

No comments:

Post a Comment