Imagine my shock, when a few years later as I began digging through materials for this project when I discovered that the captivating dot book is actually a translated text.

By: Herve Tullet

Translated by: Christopher Franceschelli

So then as I mentioned the other day, we’re back to the question of why. What has made Press Here, it’s simple illustrations in bright primary colors and easy to follow instructive text, a smashing success?

One of the most obvious answers is the interactive nature of the book and how that appeals to readers. This wasn’t lost on Tullet, who when asked how he manages to do this in an interview with the School Library Journal, responded:

“It started with my first book, Comment Papa a recontré Maman (Seuil Jeunesse, 2002). I can explain all of my books through this one. When I created this book, I understood that [there were three elements]: the book, someone who can read it (an adult), and the child. The book will talk to [both] of them. I used to say that I create empty books, or books with blanks. I knew that everybody would be able to add something. What is interesting is what they will add, the child or the adult.”

One detail that struck me about the text was that yes, it is instructional, but almost in a conversational tone. When the reader turns the page and therefore “accomplishes” the task on the previous page, they are rewarded with “Perfect” and “Well done.”

Marcus Pfister’s book was first published in 1992 (recently celebrating its 25th birthday!) and has since produced additional titles and even an animated series. And while the publisher touts the importance of the “universal message at the heart of this simple story about a beautiful fish who learns to make friends by sharing his most prized possessions” not everyone feels that is the true “moral” to the story. The book has had more than its fair share of critics who feel the need to contend the book promotes Socialism, a claim that Pfister has denied on his website.

Controversy aside, the book has sold millions of copies and so we’re once again at that point of asking why. While some claim it is the message of sharing and being selfless, the more obvious answer to me is bright, shiny and catches your eye immediately.

Like Press Here, there is an interactive element with The Rainbow Fish; the shiny scales that the Rainbow Fish is so proud of are actually made of holographic foil. If you do any bit of browsing through the comments of most readers on sites like amazon or goodreads, one thing they almost all have in common is praise for the book’s artwork. The technique of using the foil was something Pfister was familiar with from his early career as a graphic artist and which he told Publisher’s Weekly in a 2013 interview cost double what it normally would to produce a book, but that he felt very strongly about it being part of the book. It seems that sales would reflect that to have been a wise choice.

To that end it is worth noting that part of the success of Tullet and Pfister’s translated works may be due in part to the fact that the book had already proven successful in their native country. Not all books that do well at home translate into American sales, (as we’ll see in some of the series on Tuesday) but if nothing else those are the books that American publishers are probably more willing to take a risk to purchase the translation rights. Being able to promote the fact that it won awards or was a “best seller” is an additional incentive, one that will often earn it a greater marketing push.

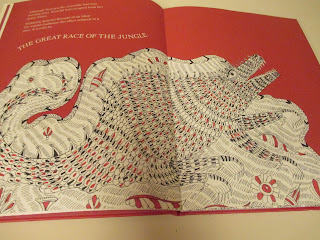

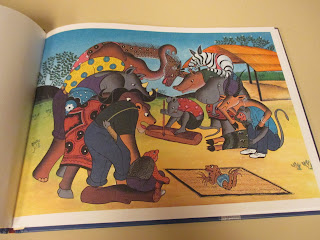

The last book that I want to share in this category, unlike the other two has not been met with widespread sales and mass market appeal. Instead, I wanted to share a title that has earned global recognition. Interestingly, it’s not even the most prominent title of the author, who became the first African writer to be awarded the Neustadt Prize for Children’s Literature in 2015. Born in Ghana, author Meshack Asare has written stories based there as well as Botswana, Zimbabwe and South Africa, which earned him the reputation of being a storyteller of the continent according to his Neustadt nominating committee. While his earlier works such as Tawia Goes to the Sea (the first African book to be translated into Japanese) and Kwajo and the Brassman’s Secret earned him much acclaim, I had a hard time tracking down copies (given that used ones were selling for near $500, it was slightly out of my budget).

I was, however, able to find at Eastern’s library and eventually get my hands on my own copy of his 1997 book, Sosu’s Call.

So my question then for this book, in opposition to the first two, is why not? If so many others (Asare’s work has been translated into numerous African lanugages as well as Danish, Dutch, German, Swedish, Japanese, Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, French, Russian) have seen the “hit” in Asare’s work, why has it not been as well received in the United States as the other two books I’ve already mentioned?

“It started with my first book, Comment Papa a recontré Maman (Seuil Jeunesse, 2002). I can explain all of my books through this one. When I created this book, I understood that [there were three elements]: the book, someone who can read it (an adult), and the child. The book will talk to [both] of them. I used to say that I create empty books, or books with blanks. I knew that everybody would be able to add something. What is interesting is what they will add, the child or the adult.”

One detail that struck me about the text was that yes, it is instructional, but almost in a conversational tone. When the reader turns the page and therefore “accomplishes” the task on the previous page, they are rewarded with “Perfect” and “Well done.”

Instead of feeling as if you’re reading the instructions to assemble a toy, it’s more as if some wise person is standing over your shoulder, allowing you to do it for yourself and encouraging your progress every step of the way. This gentle encouragement is appealing and leads to a desire to succeed, especially in children. I felt that this took the interactive nature of the book one step further than most and could possibly contribute to its overall appeal. To draw a theater analogy, this type of interaction "breaks the fourth wall," allowing the reader to become part of the text in a completely different way than most books.

If you’re a fan of Press Here, Tullet has other titles that have been translated that are similar in nature to his original splash into the American market. There’s a good chance you may come across one of them in you attend a local story time and now you’ll know that they’re part of a translated success story!

Another author, this one from Switzerland, has had massive success not just in America, but worldwide. According to his website, 49 books of his have been published and they have been translated into more than 50 languages with the total number of published copies exceeding 30 million. Similar to Press Here, I bet there’s a good chance you may already be familiar with this and have no idea that it was a translated text. In fact, I have a few teacher friends that have used this in their classroom that were stunned when I clued them in that The Rainbow Fish had to swim across the Atlantic Ocean before making a splash in the United States.

If you’re a fan of Press Here, Tullet has other titles that have been translated that are similar in nature to his original splash into the American market. There’s a good chance you may come across one of them in you attend a local story time and now you’ll know that they’re part of a translated success story!

Another author, this one from Switzerland, has had massive success not just in America, but worldwide. According to his website, 49 books of his have been published and they have been translated into more than 50 languages with the total number of published copies exceeding 30 million. Similar to Press Here, I bet there’s a good chance you may already be familiar with this and have no idea that it was a translated text. In fact, I have a few teacher friends that have used this in their classroom that were stunned when I clued them in that The Rainbow Fish had to swim across the Atlantic Ocean before making a splash in the United States.

By: Marcus Pfister

Translated by: J. Alison James

Controversy aside, the book has sold millions of copies and so we’re once again at that point of asking why. While some claim it is the message of sharing and being selfless, the more obvious answer to me is bright, shiny and catches your eye immediately.

To that end it is worth noting that part of the success of Tullet and Pfister’s translated works may be due in part to the fact that the book had already proven successful in their native country. Not all books that do well at home translate into American sales, (as we’ll see in some of the series on Tuesday) but if nothing else those are the books that American publishers are probably more willing to take a risk to purchase the translation rights. Being able to promote the fact that it won awards or was a “best seller” is an additional incentive, one that will often earn it a greater marketing push.

The last book that I want to share in this category, unlike the other two has not been met with widespread sales and mass market appeal. Instead, I wanted to share a title that has earned global recognition. Interestingly, it’s not even the most prominent title of the author, who became the first African writer to be awarded the Neustadt Prize for Children’s Literature in 2015. Born in Ghana, author Meshack Asare has written stories based there as well as Botswana, Zimbabwe and South Africa, which earned him the reputation of being a storyteller of the continent according to his Neustadt nominating committee. While his earlier works such as Tawia Goes to the Sea (the first African book to be translated into Japanese) and Kwajo and the Brassman’s Secret earned him much acclaim, I had a hard time tracking down copies (given that used ones were selling for near $500, it was slightly out of my budget).

I was, however, able to find at Eastern’s library and eventually get my hands on my own copy of his 1997 book, Sosu’s Call.

By: Meshack Asare

(Kristi's Note: Like some other titles I'm including, this is not a true translation. The book was first published in 1997 in Ghana, where the official language is English. But, must of Asare's books have been translated into other languages and the fact that it was first published in Ghana and those rights were then picked up by an American publisher for a US edition made me feel strongly about including it.)

If the fact that it was named one of Africa's 100 best books of the 20th Century (only one of four Children’s books to be given the honor) by the African Studies Center isn’t enough to make it one to add to your “must read” list, consider that it also won The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Prize for Children's and Young People's Literature in the Service of Tolerance in 1999. The award is given to “published works for the young that best embody the concepts and ideals of tolerance and peace and promote mutual understanding based on respect for other peoples and cultures.”

It is also worth noting that Asare serves not just as writer, but illustrator of his works as well and his work pays tribute to his African heritage. The boy in the story, Sosu, is disabled and cannot work, but without giving away too much of the story, I’ll borrow a review from African Publishing who called it “positive story of empowerment and overcoming limitations.”

So my question then for this book, in opposition to the first two, is why not? If so many others (Asare’s work has been translated into numerous African lanugages as well as Danish, Dutch, German, Swedish, Japanese, Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, French, Russian) have seen the “hit” in Asare’s work, why has it not been as well received in the United States as the other two books I’ve already mentioned?

While I can only speculate, I think there’s probably a few things to take into consideration. First, just because it was translated into all those languages does not mean that it was well-received or popular there either. Secondly, I think we already experience a shortage in translated works from Africa (again, for a number of reasons) and even the best of those tend to be overshadowed by their commercially more appealing counterparts from countries that publishers are more inclined to translate from (think France, Germany, Sweden and Denmark at the top of that list). I’m sure there are other causes as well. For example it doesn’t have “the look” of a more commercially successful book, meaning it may earn that “otherness” label translated books are sometimes saddled with. Whatever the case may be, Asare has proven to be successful around the world and I would strongly lobby for promoting his works to more American readers to make it “the hit” that it deserves to be.

I’ll be back on Tuesday with another set of “hits” this time looking at successful series from around the world that have been translated and published, to varying levels of success, in the United States.

I’ll be back on Tuesday with another set of “hits” this time looking at successful series from around the world that have been translated and published, to varying levels of success, in the United States.