An average picture book comes in at around 500 words. And we all know a picture is worth a thousand words. So what does that say about a wordless picture book? And for our purposes here can we consider a book without text to be translated?

From the beginning, I have steadfastly lobbied for the inclusion of wordless picture books into this project. To back me up, I consulted my old friend Noah Webster who offers up the following:

Translate

1a: to turn into one's own or another language

Ah that Noah, he never lets me down! By this definition, not just international wordless books, but ANY wordless books could be considered translations. The reader of these books is turning the pictures on the page into their own language – translation! More so, the reader is not just turning it into their own language, but their own story. You could “read” a wordless picture book repeatedly and not ever tell the story exactly the same way twice.

From an educational standpoint, there are endless opportunities to use this type of book with any reader, at any age with varying different language skill levels. When it comes to younger readers it can be an opportunity to build their vocabulary. A study by professors Sandra Gilliam, Ph. D. and Lisa Boyce, Ph. D. from the Emma Eccles Jones College of Education and Human Services at Utah State University showed that mothers used more complex language when sharing a wordless book with their children than they did when they made comments while reading a book with words. Older readers, as the website Playful Learning notes, learn how to think more deeply and critically about plot elements, the interaction among characters, cause and effect, the tone of the story, and the intended theme.

It wasn’t until an assignment a few years ago in my Children’s Literature lecture that I fell in love with wordless picture books. We were assigned to write an analysis of any picture book that had been awarded the Caldecott Medal or a Caldecott Honor. One of my favorites, The Three Pigs by David Wiesner, was off the table because we had read it in class. Undeterred, I decided to check out one of his wordless titles, Tuesday. On a whim, I sat down with both my kids separately and asked them to tell me the story. I was floored by how different their versions were from each other and mine as well. One particular two-page spread still sticks out in my memory:

Are the frogs chasing the dog? Is the dog afraid? Are they playing together? Is the dog leading the frogs someplace? The dog only has one paw on the ground, is he learning to fly with the frogs? Are the frogs trying to capture the dog?

I could go on, but you get the point. I was fascinated by how each person could read and tell the story differently based on their perceptions of what was on the page. Further, how that could change depending on what the reader was noting during that reading of the story, what drew them in at that particular moment, intrigued me.

When I began this particular project, I began to think more about how images, color, line, shape, texture, shading, size – all those pieces that go into creating an illustration – change not only reader to reader but culture to culture as well. I found this fascinating article from the Huffington Post about color meanings in different cultures. For example, an illustrator in America may use yellow as a bright and cherry accent but when viewed in France it may be associated with betrayal as dating back to the 10th century, the doors of traitors in France were painted yellow. Or what about orange? It is the national color in The Netherlands, associated with wealth and the royal family. But in Egypt, it’s often associated with mourning and in Columbia, it represents sexuality and fertility.

I mention all of this because it will be something to be mindful of over the next few days as we examine wordless picture books from around the globe. It is very likely that readers from different cultures may miss the intended meaning behind certain choices the illustrator made. But that’s OK! In fact, that’s one of the reasons that I most wanted to include these books. Like many of the translated books we’ve covered so far, there is still that “opacity of other cultures” in these books. Some of them still may seem “strange” or different from what we as American readers are used to. But with these, we aren’t held to the text on the page to convey the story. We shape our own; we translate the images into our own story, making it as “strange” as we want it to be.

As a reminder, here’s how I originally introduced this category when we started:

“While it may seem like an odd choice, after reading so many books I felt very strongly about including the “Wordless” category. The more books I read, the more I realized just how different this project was because it specifically analyzes picture books. Pictures are an entire language of their own! I have developed an entirely new respect for the complexity of picture books through this project. While the words themselves they contain are translated from one language to another, the pictures remain the same but the way they are “read” by an audience does translate them in my opinion. Subtle details, colors, lines, and choice of perspective view can be translated differently by a reader of the original book as opposed to how they are viewed by someone from a different place and culture. When pictures speak a thousand words what language are in they in?”

In a perfect world, or perhaps when I have more time to tumble down this particular rabbit hole, I think it would be fascinating to find out how young readers from different cultures “read” any of the books that we’re going to spend the next few posts looking at. How does a reader from the source country tell the story? What is important to them? What about a reader from another country? What aspect of the stories are similar and what are different? Do they give different levels of importance to different aspects of the story? Do they notice different themes? As I noted in my story above, even my own two children have vastly different interpretations of just one image from Wiesner’s book – can you imagine the range we may see worldwide? Again, just some things to consider over the next few days.

While I’d love to spend days and day diving into these illustrated gems, I decided to limit this category to only three posts. On Friday we’re going to look at two books (both of which are series!) that follow a style that is reminiscent of a comic book for younger readers. Then on Tuesday, we’re going to focus on three books that bring in an element of play and imagination. But because I love this style so much I wanted to share a few others that I found here briefly to wrap up today’s post. Enjoy these and then I’ll see you back here on Friday!

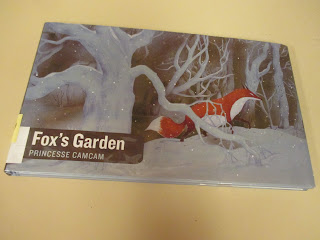

By: Princesse CamCam (aka Camille Garoche)

For more information, I suggest checking out this review from the website Brain Pickings in which Maria Popova discusses the story and illustrative techniques Garoche uses. She even likens it to another book we covered here, My Fathers Arms Are A Boat, illustrated by Øyvind Torseter.

By: Benjamin Chaud

I love this book by French author/Illustrator Benjamin Chaud which reminds me of an animal “Where’s Waldo?” with the bear cub racing after a bee through the forest, city and an opera house. Chaud followed up with two more similar wordless titles about the little cub, Bear’s Sea Escape, and Bear’s Surprise. This interview from Picture Book Makers with Chaud is incredibly insightful as is this one with Betsy Bird from School Library Journal about all of Chaud’s work, including a few with text as well.

By: Sylvia Van Ommen

Remember a few weeks ago when we talked about Jelly Beans? This is a wordless title from Dutch author Sylvia Van Ommen. The story made me smile, so I don’t want to give it away, but you can check out a full review from Publisher’s Weekly if you don’t mind the ending being spoiled. If you liked Jelly Beans this is a fun comparison. The book is in full color, unlike the black and white line drawings we saw before, but the strong message of friendship still resonates.

Hailing from the Netherlands, father and daughter writing team Ronald Tolman and Marije Tolman won the 2010 BolognaRagazzi Award for the most beautiful picture book in the world with The Tree House. The followed it up a few years later with another wordless title The Island. Both of these are what I would consider “thinking” books. The book is wide open, even more so than the others I’ve mentioned here, to imagination and interpretation. For more information, I suggest checking out this review by one of my favorite websites, Children’s Book-A-Day Almanac or this one from Women Write About Comics.

No comments:

Post a Comment